Project - DIY Constant Current Load

A simple yet essential part of any electronic test bench. A DIY Solution.

Description

Constant Current Loads are an important part of a testbench when working with power supplies. They allow the testing of the various parameters of a PSU in a controlled fashion.

This project takes a look at a simple DIY solution.

Details

The Problem Statement

I have recently been doing extensive experimentation with recycled batteries as well as voltage regulators and line control circuits. The customary approach requires a programmable DC load to the connected such that the output can be tested under various conditions. Unfortunately, these commercial solutions are quite expensive in addition to being big and bulky. Due to a constant fear of the spouse with regards to unexplained expenditures as well as a lack of bench space, I set out to find a DIY solution to the problem.

The Search

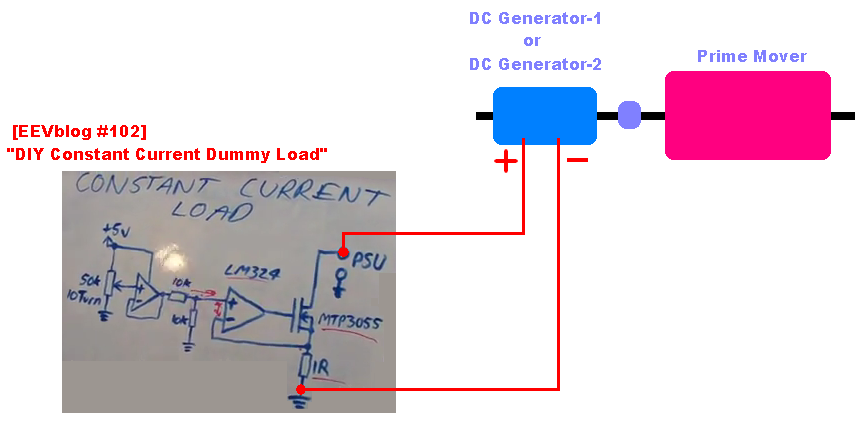

Doing a google search for ‘constant current source’ comes up with a number of interesting results including publications in instructables. Though these may not inspire much confidence, they are a source of test data that an approach was in fact used. My search lead me to a youtube video by Dave Jones of the EEVBlog where he uses a simple circuit to make a DIY Constant Current Load. Further investigation revealed that many more had tried the approach and indeed was a usable. Hence, I decided to recreate the circuit shown below due to it’s simplicity.

The Design Changes

The selected low-side sensing and control approach was solid however, I had to improvise a bit in my approach with the first change being the MOSFET itself. The MTP3055 was not something I had to hand so I decided to use the IRFZ44N. This had a cascading effect on the design with the Vcc being migrated to 9V and eventually two 9V cells. I used the LM358 which is half the op-amp the LM324 is however retains all the characteristics. Lastly I only had 1/4watt resistors which I had to make do with but did not make a big difference in the long run. I also did not want to spend on a dedicated meter hence resorted to other means. The final improvisation in the assembly is the use of a multi turn preset in place of the suggested multi turn pot which is cheaper and more compact.

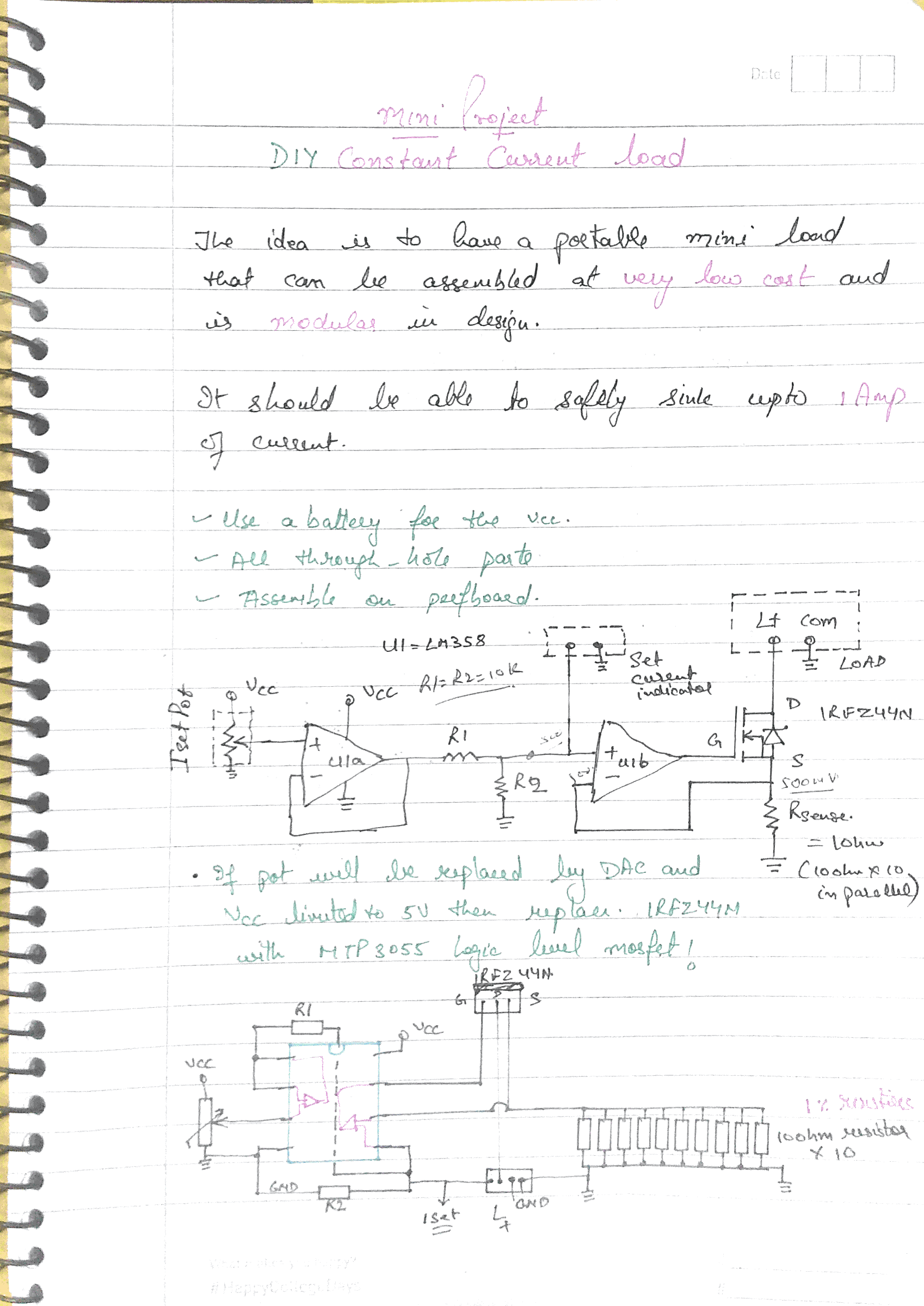

The Circuit Diagram

Below is a shot of my notebook with the circuit diagram, specs and a layout. I used separate connectors for the Op-Amp supply and the load. In order to monitor the set current, tapped into the non-inverting input of the second op-amp. This connected to a multimeter would give us the set current without the need for a dedicated meter thus reducing the BOM cost of the project. An extension of this technique could tap into the inverting input to get the value of actual current being drawn. In my case, I employ a dedicated meter for the task to ensure accuracy.

Adding a fuse or switch seemed trivial though can be a useful feature. I do not plan to make a PCB for this since it is a stepping stone to the next level which I will discuss at the end. I made a layout of the design before I switched on the soldering iron so that I knew exactly what I would be aiming for. I aimed to made the device as small as possible and in true DIY fashion.

Assembling The Device

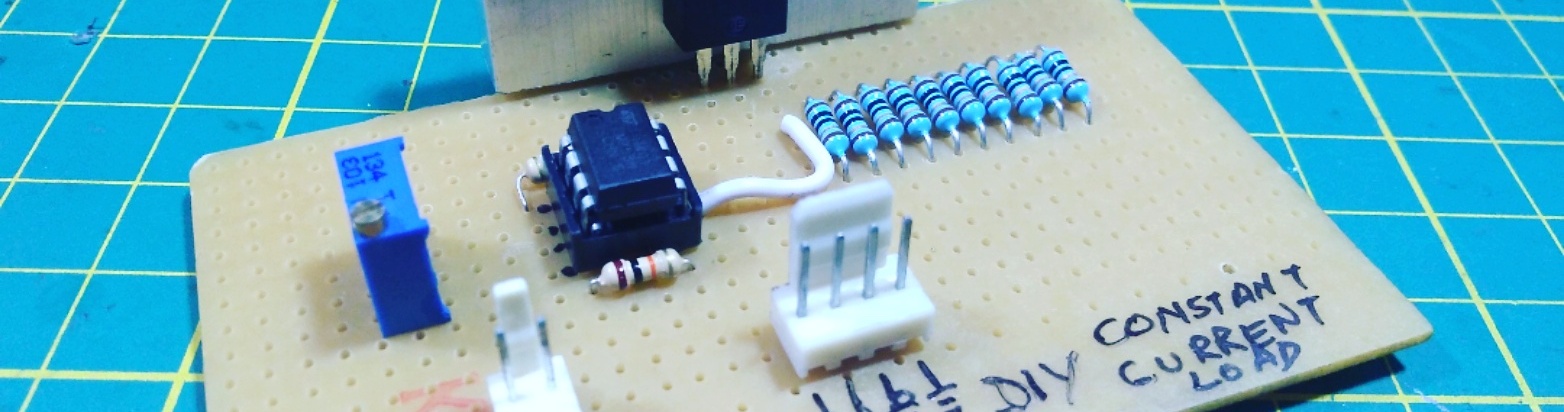

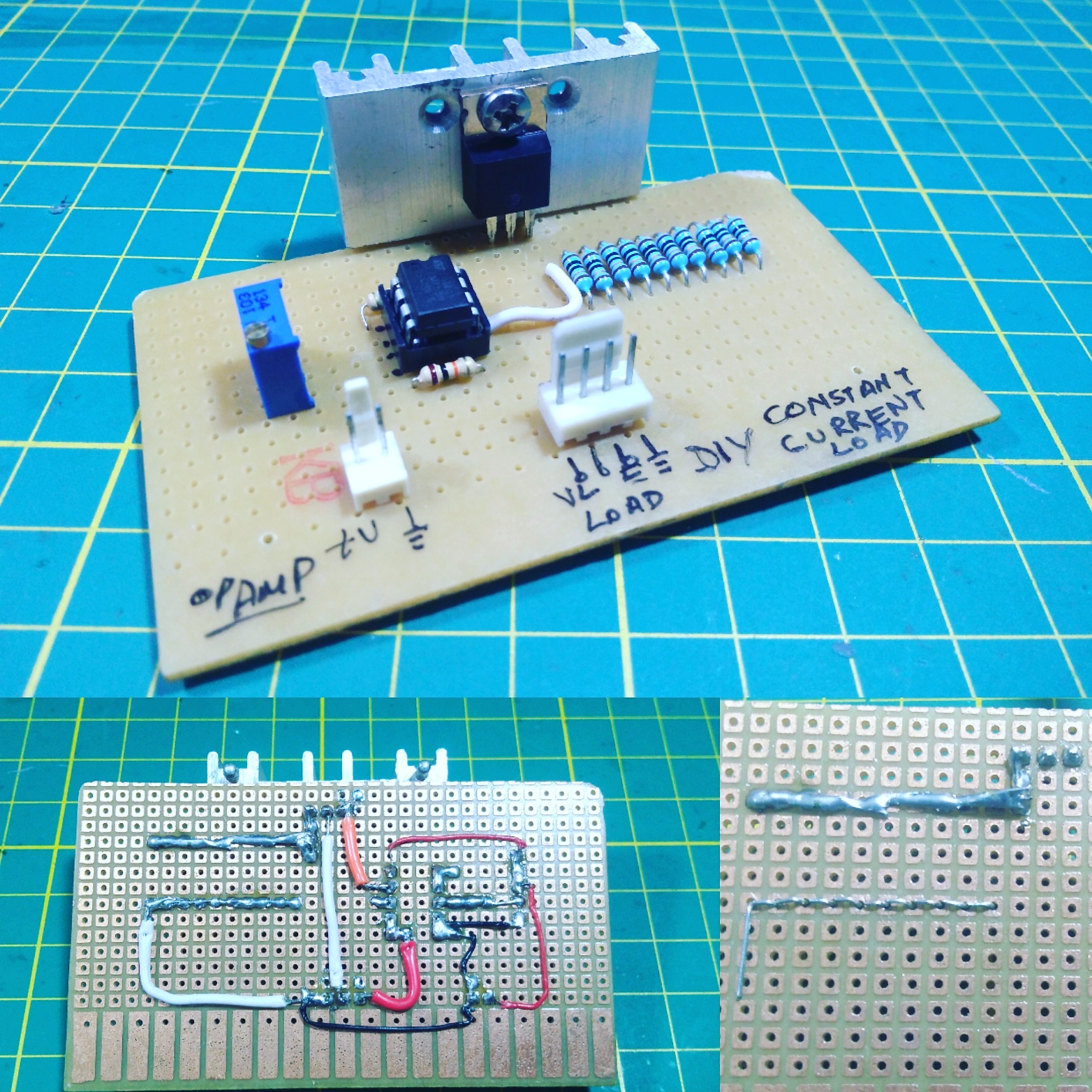

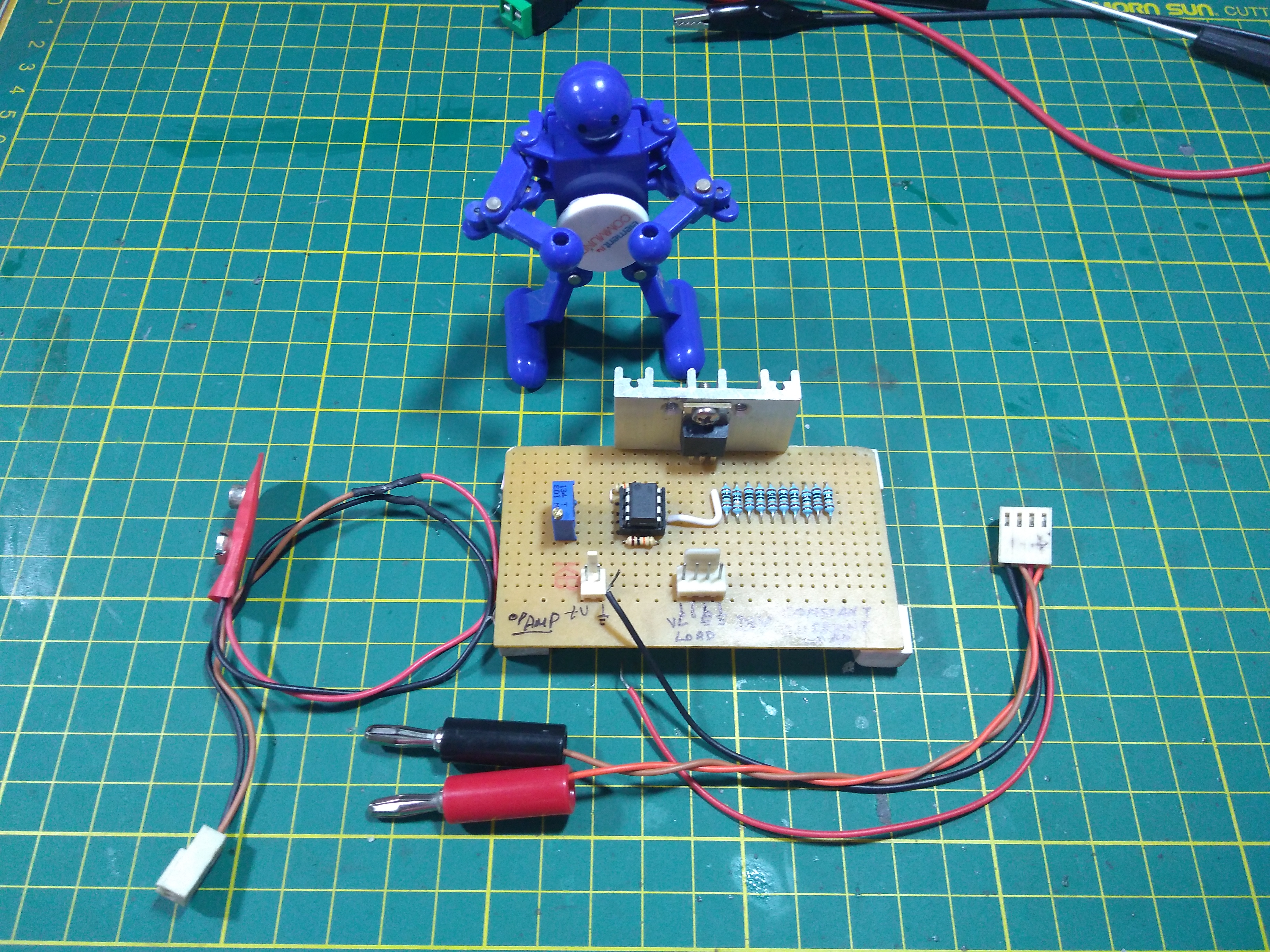

Putting humpty-dumpty together was not a challenge thanks to a bit of planning and the end result is presented in the image below.

With my 3D printer lacking the necessary filament, I decided to add some DIY stand offs to the resulting circuit board. Pencil erasers cut up in the right size and attached using hot glue were a successful endeavour allowing for a bit of ground clearance. This would be helpful in case of solder blobs or unsheathed wire trims were loose on the workbench. The heatsink was a non branded one though it did seemed big enough and did it’s job well. The end result is shown below without it’s connectors as well as in complete setup.

Testing

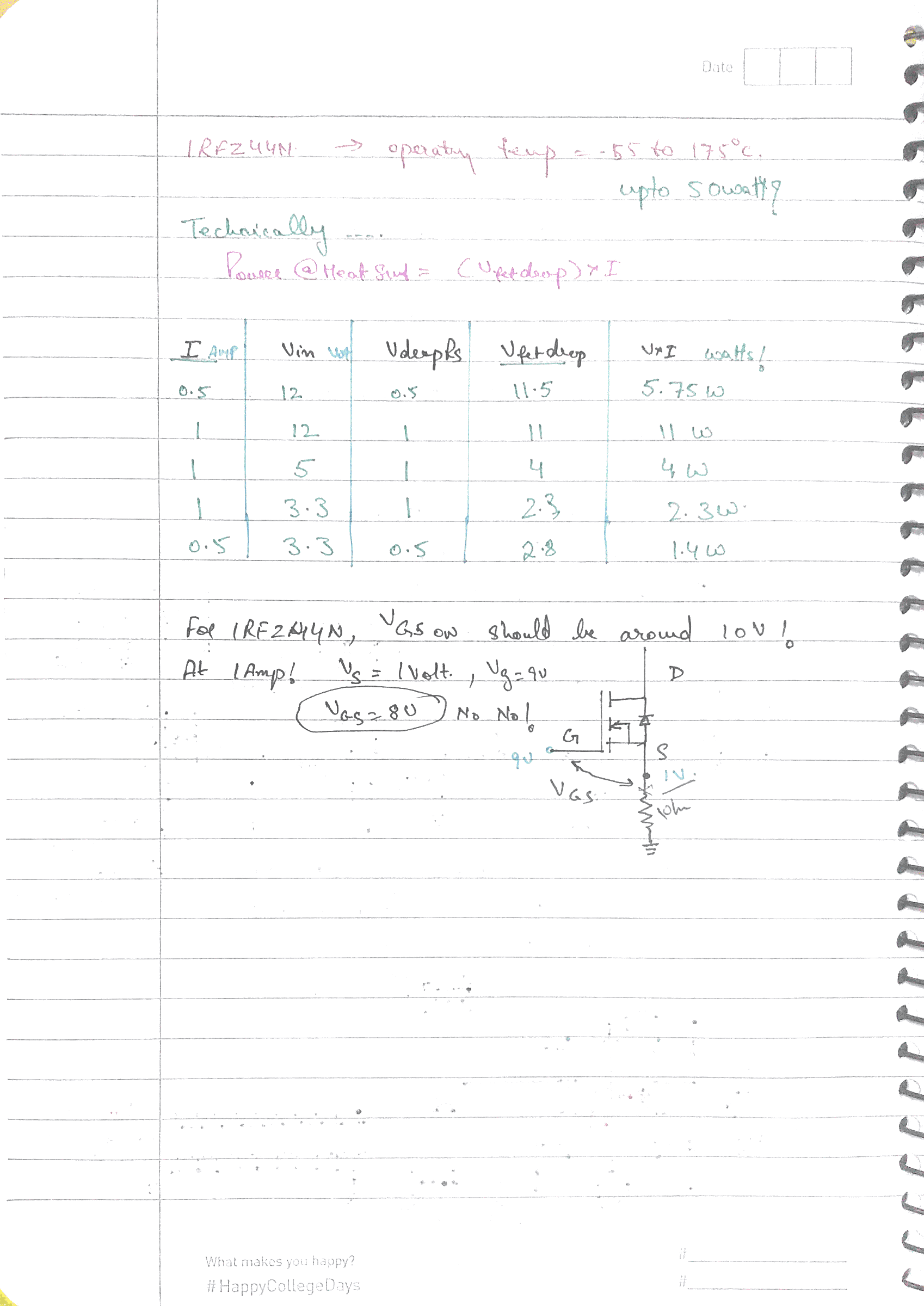

My tests were conducted with a Tenma Bench Power supply at 12 Volts though I did do the math before hand. Below is a capture of my workbook reflecting the same.

Sincethe IRFZ44N is capable of working up to 175’C and 50Watts, my tests would be a piece of cake. Below is a video of the entire project along with a demo of the final product.

Video Demonstration

One point to be noted is that at 1 Amp of current, the drop on Rsense would be 1 Volt and with the Vgs required to be more than 10V for the IRFZ44N and 4.5V for the MTP3055, the gate voltage should be as high as possible. This would also go on to effect the switching times with the Vgs rise time not being able to meet it’s intended mark.

Lessons Learned

I designed this module to work as a standalone project however there are a number of things that can be done in the future. The first being the addition of an Totem-Pole Driver stage to the MOSFET to increase switching speed. This is easier said than done however it addresses the issue raised in the previous section.

The second modification is using a DAC to digitally control the set current. The buffer could be converted into a gain stage and it could be digitally controlled. Next would be the addition of an ADC to monitor the actual current flowing. An INA219 could be used directly if the circuit were to be made anew and on a dedicated PCB.

Lastly, a self resetting fuse and temperature sensor could be a handy feature for long term use. A DS1307 could be used for the RTC and store current and voltage data until it is retrieved. This could be furthered by the addition of a memory card hence the possibilities are endless.

This is a quick and dirty solution for the procrastinating maker and enthusiasts and I hope it finds use in your hobby shop.

Happy Hacking!